I was fired from my first job because I am Gypsy,” says Renata, the only Gypsy lawyer in the largest Gypsy camp in Ukraine. After graduation from university she was trained in the local civil registration office, but even after successfully passing all the exams, she was refused a job.

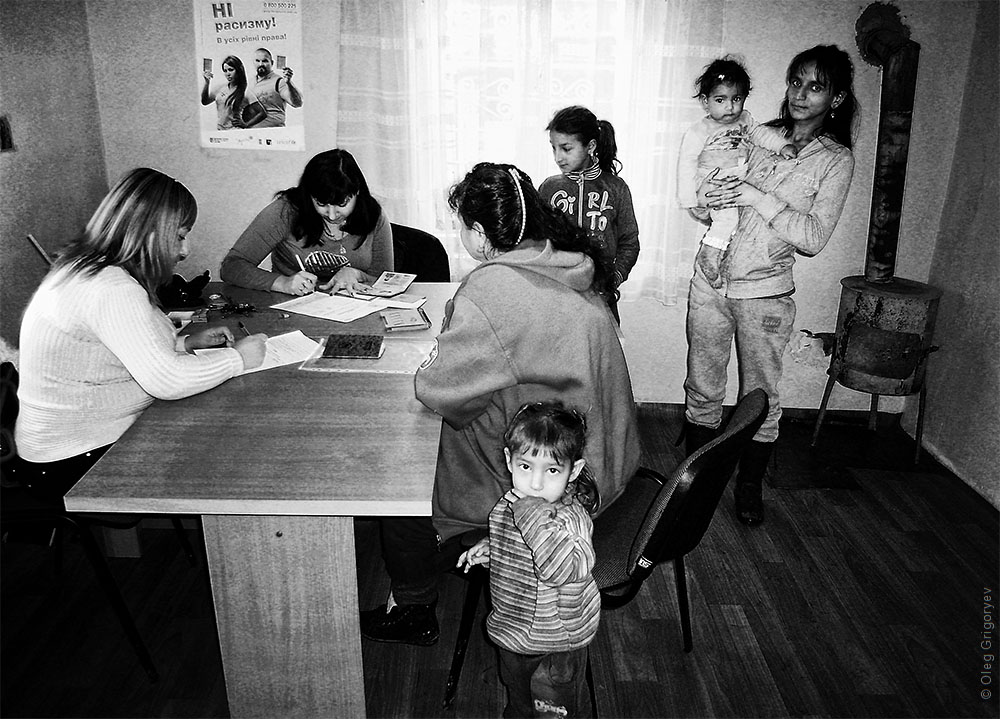

A plump woman enters the office with her 14-year-old pregnant daughter, they sit on chairs opposite the table at which Renata meets them and ask for help in paperwork. Renata got used to such requests, most frequently visitors ask for assistance in obtaining social allowance, obtaining a birth certificate and passport.

Actually, the organization office, where Renata works, is one large room of the house where she was once born and raised. The building was plastered, linoleum was laid inside and the walls were painted in an optimistic light yellow color. In the light room there is a large table, chairs for visitors and a small stove, on the walls there are newsletters and a large painting depicting a dancing Gypsy girl in a traditional dress.

The woman, who came to the reception, explains that her daughter needs to apply for social assistance to care for her unborn child. Renata exhales heavily and tries to explain to the woman that her daughter does not have documents and in order to receive social assistance, she must first legalize in Ukraine, that is, receive a birth certificate and a passport. And only after that she must apply to the social protection department for assistance, because both her daughter and her child are still invisible to Ukraine.

There are many similar cases in the camp, because early marriages are traditional for the Gypsy – starting at the age of 12-13, and then early pregnancies. For society, such a practice is savagery, but to convince the Gypsy that their centuries-old custom causes irreparable harm to girls and young families, in general, deprives them of the possibility of a better life in future is an almost impossible task. Renata is also trying to prevent early marriages and explains to the woman the risks girls might come across in this case.

Girls actually skip adolescence and from children immediately turn into young mothers with non-childish responsibilities, not to mention the fact that early pregnancies significantly affect health. Girls, like their young husbands, are forced to leave school, which means that they never get an education and actually put an end to their future, they are going to get only low-skilled work, poverty and lawlessness.

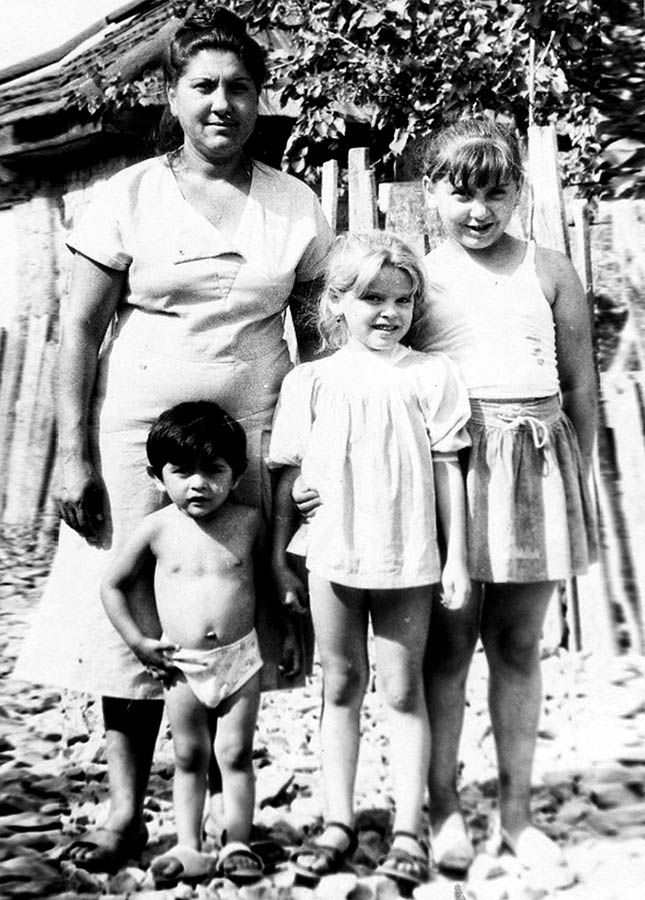

“My mother played a decisive role in my life, it was she who instilled in me a culture of education early on, she understood that this was my only chance to make a career, she wanted a better prospect for me,” says Renata. – After 9 classes of school at the age of 16, she went to work as a cleaner at the Mukachevo railway station. People from her work, realizing her potential, gave her parents an ultimatum – either her mother goes to school, or she will be fired from her job. So she entered the Lviv University and received the specialty of a crane operator, whom she worked for about 30 years. She did her best to instill in me the conviction that without education I would not be able to break out of the Gypsy camp and build a worthy future for myself and my children.

I realized that the environment plays an important role. When I went to a Hungarian school, I constantly heard in the camp from our people – why are you studying, you won’t become anyone anyway, you will sweep the streets, they don’t give ranks to people like us. It infected me with despondency, it was a shame to study. And in the city where I moved to continue my education, everything was the opposite – instead of walking on the street, the children learned their lessons.

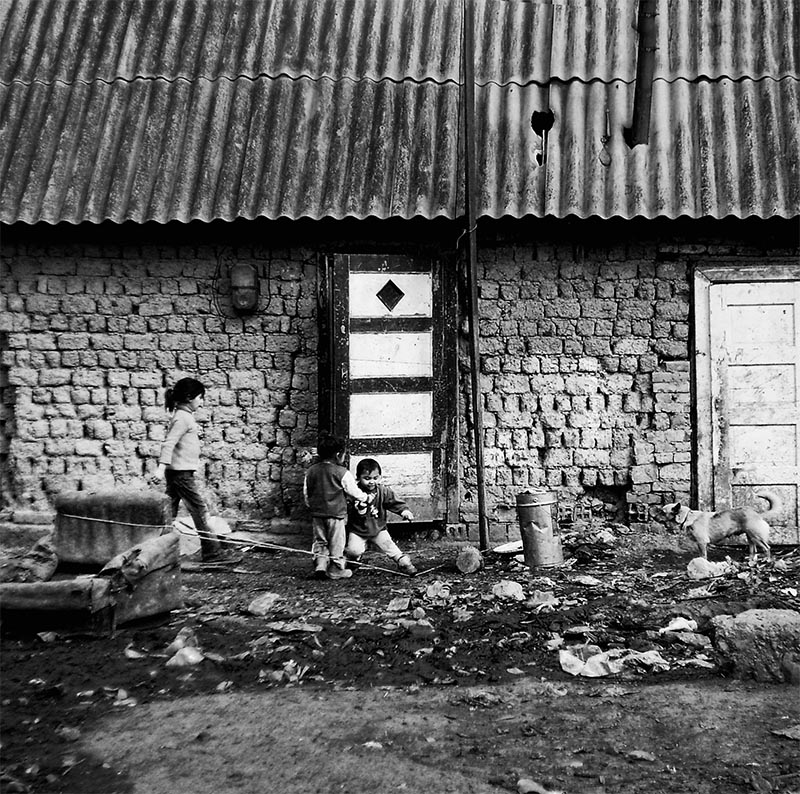

I was born in this camp and lived until the age of 13, I played on these streets as a child, my great-grandfather and great-grandmother and the whole family on the maternal side lived here. I remember that time: it was a cheerful, carefree life, we rejoiced with each other, celebrated together, sang, danced, cooked bograch on the street in a large cauldron on fire. I tried to follow the understandable way of life that was before my eyes. This is exactly what everyone else does, with a few exceptions.

Renata looks for the required document in a pile of papers, enters the data into the computer and searches for the necessary information. She maintains strict order in documents. Her concentration is interrupted by a man in old clothes and dirty rubber boots, who has just entered the room: he is trying to explain from the threshold that he was illegally fired from his job two years before retirement. Renata listens to the person and reassures him – she will definitely help. The inhabitants of the Gypsy camp are used to being constantly refused and literally pushed out of the threshold of state institutions, they are treated like garbage.

The voices of a living street are heard from the outside to the office – loud conversations, children’s laughter, a mixture of Gypsy, Ukrainian, Hungarian languages sounds. The Gypsy speak the same language all over the world, but different countries have their own dialect.

“The Gypsies have been trying for centuries to survive separately, to preserve their customs, jealously guarded them, the Gypsy community is very complicated, but at the same time extremely bright. A wedding in the camp is so bright and unforgettable that there is no other way. And the guys are incredibly generous. I went on dates with both Gypsies and Ukrainians, – Renata smiles, – I can compare.

A Ukrainian guy “counts money”, and a Gypsy guy, when he takes me to the best restaurant, says: “Order whatever you want! I will buy everything for you!” Renata laughs a little embarrassedly. – The Gypsies are a special sincere people. And there are still many stereotypes and unrealistic ideas about us, but contrary to all the fables, today’s Gypsies no longer steal horses, train bears and are not first-class blacksmiths, as before.

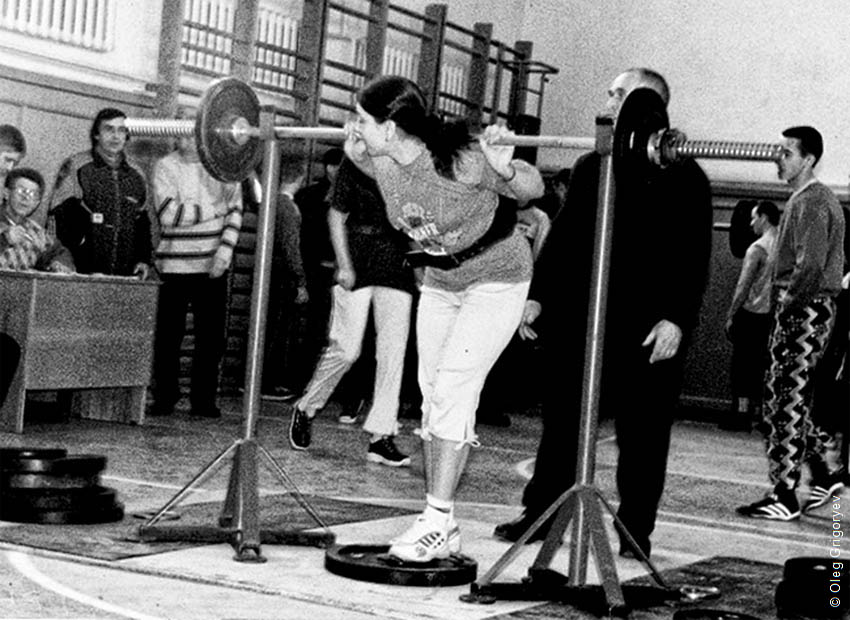

Renata finds and shows on the computer a photo of how she, along with other lawyers and activists, is conducting an advocacy campaign. And also a photo of her school youth – on one of them she lifts the barbell – Renata is a two-time powerlifting champion of Transcarpathia. She can talk for hours about Gypsy people and their habits.

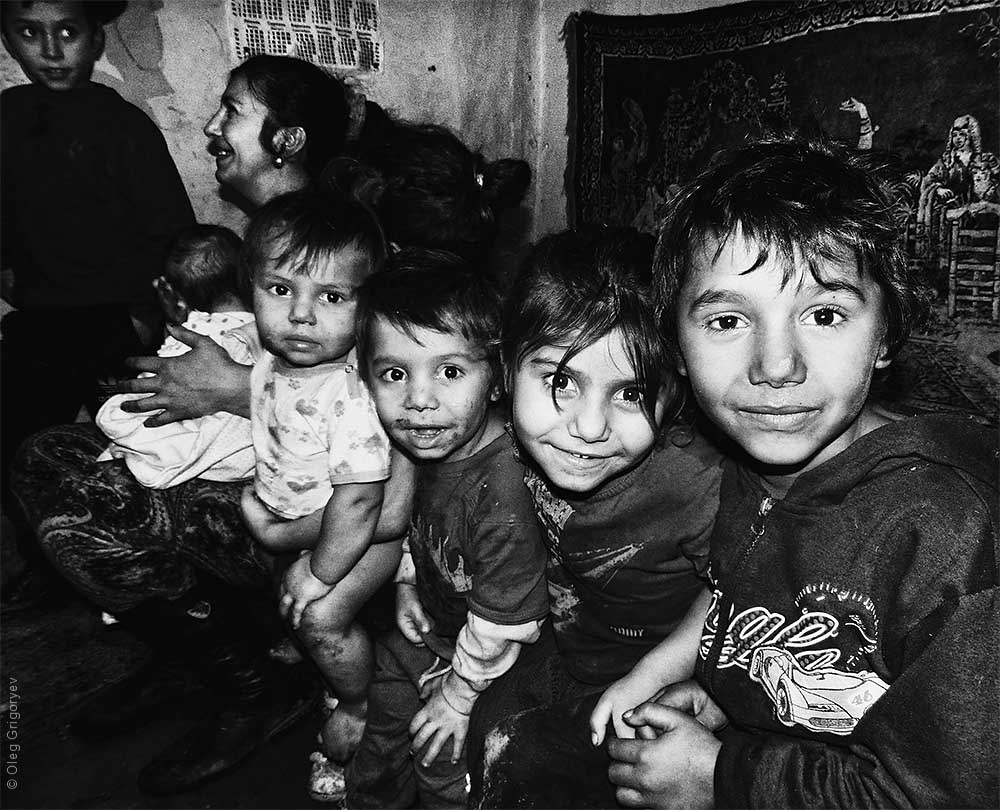

“From everywhere you constantly hear: “You Gypsies are not capable of anything, just sweep the streets.” I am very sad and hurt when people are aggressive towards the Gypsies. They are considered parasites that live off taxpayers, criminals, carriers of diseases, and beggars. Even in fairy tales, a gypsy is always a negative or comic character. This stigma remains on them today. Everyone looks at us as people from the untouchable caste, both in Transcarpathia and in Ukraine as a whole. There are more than 120 places of compact residence of the Gypsies scattered across Transcarpathia, and all of them are isolated, persecuted, deprived of rights and written off from the account. Only a few manage to escape – these are those who go to study further.

“I remember there was a case when I was still studying at the university as a lawyer, classmates asked me if I could guess. I answered them: “Of course not, but my mother told me that they went to my grandmother every day and she knew how to do it … I didn’t get it,” Renata laughs.

People from the camp come to Renata not only to solve their problems, but also just to talk or bring their children so that she can teach them how to write. Children always sit at the table, pencils are scattered in front of them, and they draw something on paper. One of the girls seriously decided to follow the example of Renata and become just as successful, she listens to what problems the Roma come with and carefully watches the lawyer.

“She will be my assistant when she grows up,” Renata laughs. – She says that she also wants to become a lawyer and help people, just like me. She is very smart and capable.” – The girl was a little embarrassed by such attention to herself, but after a minute she was waving her legs cheerfully, sitting on a chair, and drawing something with a pen on a white sheet of paper.

“You know,” he tells me, “because of the lack of education, the Gypsies do not know their rights or obligations, and, therefore, their opportunities. Many of them still do not know how to read, write, or even put their signature on the form. A significant part of the Gypsies do not even have documents, and without them, in fact, a normal existence is impossible. However, I am glad that now more and more Gypsies begin to realize that without elementary education they are absolutely unprotected, neither socially nor legally, and this entails unemployment and poverty”.

Renata continues: “The Gypsies still have an imaginary fear that they will lose their cultural identity and traditions. Most of them live in isolation, few of strangers dare to enter the camp. They live in conditions that no one would agree to. The Gypsies are afraid, in the news, if someone stole something, then it is definitely Gypsy, so it is not surprising that other people bypass us. They are afraid, they don’t want their children to study with the Gypsy, and even worse, they are very aggressive”.

Renata is offended for her people, she is rooting for them with all her heart and soul and is trying to somehow change her attitude towards the Gypsies by her example. And she believes that even with small steps, the situation will change for the better.

“I always and everywhere say that I am Roma. And I don’t need to say that I am Hungarian or Russian there, as many people tell me. Not! I am Gypsy. And I’m proud of it. And I want there to be more people like me, so that they are proud”.