They are erased from ordinary life and forgotten, their photos won’t get into family albums – you really have no chance to see their photos at all. You will never know about their problems and never hear their dreams – the closeness and remoteness of boarding schools leaves no chance for it.

These children will never say the word “mother”. Nobody calls them by name because everybody uses the diagnosis instead. The children in this psychoneurological boarding school will never go outside and only few of them will live to reach their full legal age.

I watch the babysitters rushing through the hallways, they run off their feet. There are 7-10 children per one babysitter – they need to feed, wash, change clothes or put a child in a wheelchair. Given also that children are unhealthy, each of them has a long list of co-existing diseases. Some children are too active and shout constantly, the other ones are too quiet and lifeless – they look up at the ceiling all of the time. A child may not know who is to their left and to their right, who is making gurgling noises and who is shouting. The sides of the beds are covered with “bumpers” – special blankets. A girl with hydrocephalus screams because her head constantly hurts from high intracranial pressure. A boy with cerebral palsy makes gurgling noises because he can’t swallow all saliva so he splutters as a result.

I enter a small room with a narrow small window in which there are a lot of tightly placed beds with children. The atmosphere in the room is inseparable from the specific smell that is simply impossible to forget – the pungent and persistent smell of urine and disinfectant solution. You get used to it not immediately and this smell firmly binds in your memory with what you have seen.

I get closer to cribs and look over the sides. Some children don’t react at all and don’t focus on me. Someone smiles immediately at my appearance and awkwardly stretches their hands controlling their movements with difficulty. There is almost a reflexive desire to stroke them, to respond to their movements somehow.

‘Get away from the crib! Don’t touch the children!’ says an irritated nurse, raising her voice from whispering to screaming.

‘Why?’ I ask in surprise. But then I guess what the reason is.

‘When you come close to them, they see a person and start waving hands and making noises. It’ll wake up others. I can’t calm them down. And I still have a lot of work to do – wash the floors, change the beds and clean the toilets. I have only two hands!’

Nurses and babysitters are so burnt out, morally and physically exhausted from work with heavy children that they don’t communicate with them at all. They no longer talk, they shout. They don’t hug children, they turn them like bags of potatoes, trying not to feel, not to think, not to look closely. If it’s necessary to calm down the child with cerebral palsy who from constant lying already shows self-aggression, they will fill them with neuroleptics. It’s faster and easier.

I freeze with horror at the thought: if only these children knew the depth of their own pain and could realize the injustice of life, they would cry bitterly. But they don’t know how to cry, they lost this ability after their mother abandoned them in the maternity hospital. Since childhood, the system sorts people into subspecies and distributes them to special institutions. This is a terrible and unchanging reality.

The staff doesn’t understand that a boarding school for a child is not just a place where they receive treatment. It is their only home for life and that’s why children should be spoken to and taught. If a child with Down syndrome is lying all day in a room in which he or she can’t hear speech, then a child can’t imitate it and will never learn to speak, even though he or she potentially has that ability. When such children are together and if you talk to them all the time, they learn fast enough.

These children don’t need a psychoneurological boarding school. They need specialized medical care, trained staff, the creation of a “developing environment” and conditions close to those at home as it has been done for many years in the West.

The director of the boarding school who is a caretaker for 140 children also doesn’t understand it. Think for a moment, how you can know and remember not just their names, but the needs of each one, specific requirements, protect their rights and buy the necessary medical equipment. The director is an 82 years old man with arthritis and oncology but he’s got his claws deeply into his chair and he doesn’t care about reforming, as long as all the beds are full. According to the staff schedule, there is not a single special education teacher, not a single rehabilitation therapist in the boarding school. Instead of five doctors, there are only two and there are a lot less nurses and babysitters than needed. The children became hostages of the director.

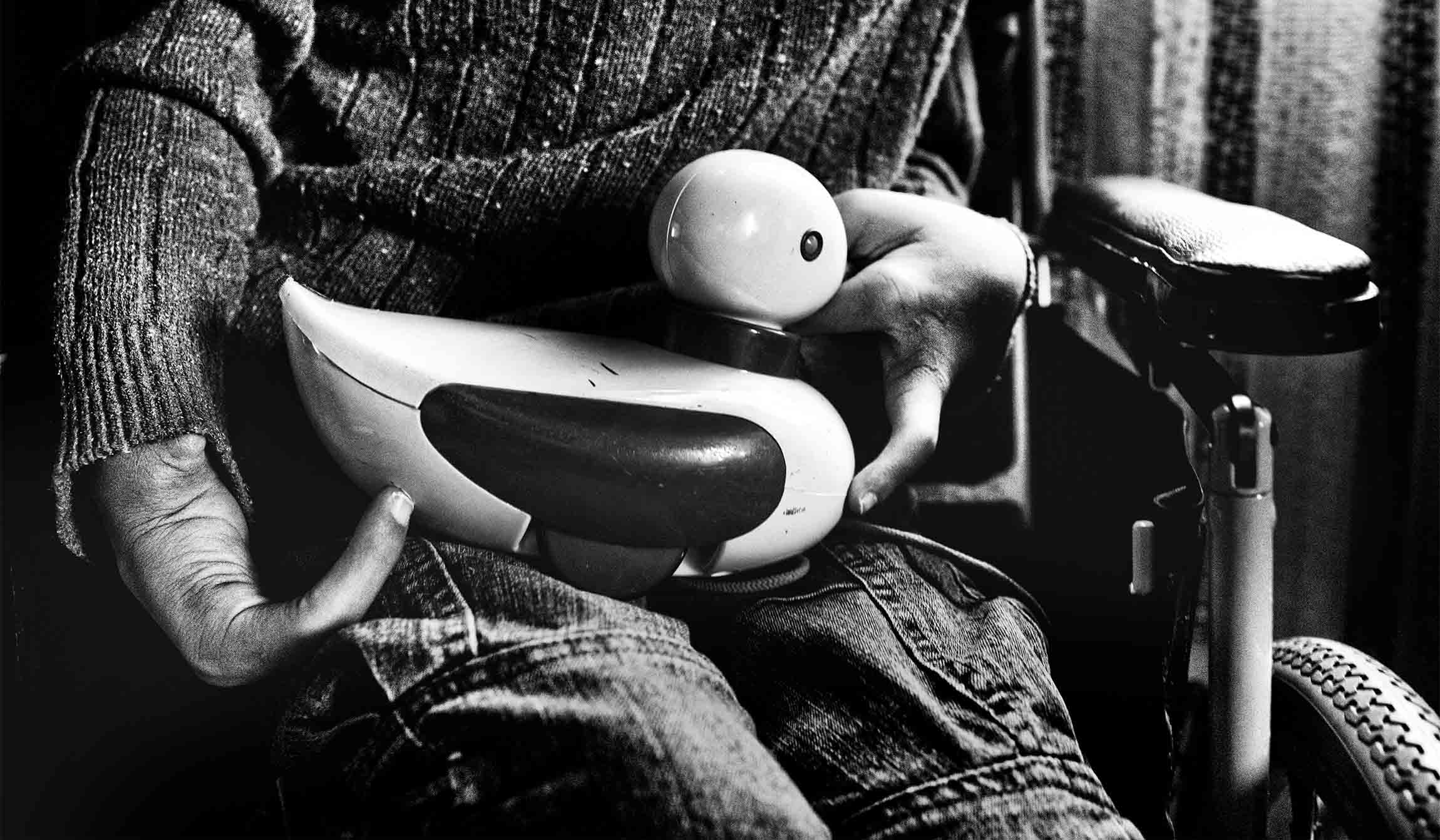

Going up to the second floor, I’m walking down the hallway with bare walls. I see three children sitting in wheelchairs in a row with their backs facing the wall. I notice that one child is tied to a wheelchair. I ask why it is so and who tied him. The nurse looks at me very surprised and answers:

‘He has cerebral palsy. He slips off the chair all the time.’

‘Why tie him up?’ I repeat my question.

‘We’ve accidentally bought a chair for an adult and it’s too wide. That’s why he slips down constantly. What’s not clear? That’s why we tied him up.’

This ugly, inhumane boarding system is designed to maintain a poor quality of life. It’s a relic of the last century that still can’t die out, remaining a place of torture and humiliation.

Monitoring visits to psychoneurological boarding schools of the fourth profile for me are the most difficult and emotional. When you get out of there, you carry with you some of that silent pain. You feel broken and devastated. But you know, these kids feel a hundred times worse than you. You leave such institutions also with rising irritation and anger from indifference of the management and the staff to the children.